light as a common thread

john hogan: on craft, design and ideas for first light

All visual art relies on light. Glass art is perhaps unique in its relationship with light, capable of capturing, reflecting, transforming and empowering its expression, altering it within to transfigure both its own surface and the space around it. Artist John Hogan has sought in his practice to discover the softer, gentler side of light, seeking ways for his artwork to “stay out of the way” and let the beauty of light express itself.

Finding a language and expression in his work that keeps quiet and allows light to be of focus, is central to his art. Hogan believes that “in an era of technological belligerence, with our short attention spans, art can form anchors for the mind.” In his view, the best art incites needed moments of stillness. Hogan offers his personal experience of the Rothko Chapel in Houston as an example: “When there, you are not able to connect directly to life’s experiences, so you kind of float in a cosmic gel. The truly new is something without connections, something that is raw, forcing an interaction.” Hogan believes that art can create portals or connection points, places where the material can link with the non-sensory experiences of reality.

The prospect of working with Westbank on First Light, a project spanning a quarter of an entire city block, is an unprecedented chance to test the experience of glass art at the building scale. Hogan’s work for the past 15 years has been extensive but of a finer grain; this new commission raises many new but interesting challenges. More so than earlier experiments in architectural collaboration, the installations on First Light will require innovation, creativity and a far greater scope. Hogan is interested in the creative challenge of how art work, spread throughout the project and around the entire podium, can open up new possibilities for glass art. “This is definitely a ‘big picture’ approach to art-making – something I’m looking forward to exploring further.”

John’s work will be incorporated throughout First Light: in veils around the podium and the amenity space, in the residential lobby, and in a secret garden on the roof. His current designs for the podium veil feature digitally-cut disks of tempered glass strung at intervals along lengths of steel cable, set in tension on all sides of the podium, but having minute vibrational movement in the wind. Each glass disk will act as both prism and reflector – every one of them a unique landing point, interacting with the light that strikes it in different ways at varying times of day and season. The glass will not act as aloof works of art, but as permanent architectural elements that will also form an integral layered detail, part of a larger visual ensemble. They rise to the challenge of evoking the look and feel of a veil, draped and flowing

over the architecture.

Echoing the sentiment, Westbank and James Cheng began with their own exploration of layered screens. Much of Hogan’s work reflects the idea that sometimes you want to look through things, not directly at them. He is most interested in how this new work for First Light will be perceived as one walks or moves through the city. “I hope that when it is seen obliquely, it will be as if you’re driving late in the day along the side of a lake – you are moving, the water is moving, perspective and multiple light points are moving.”

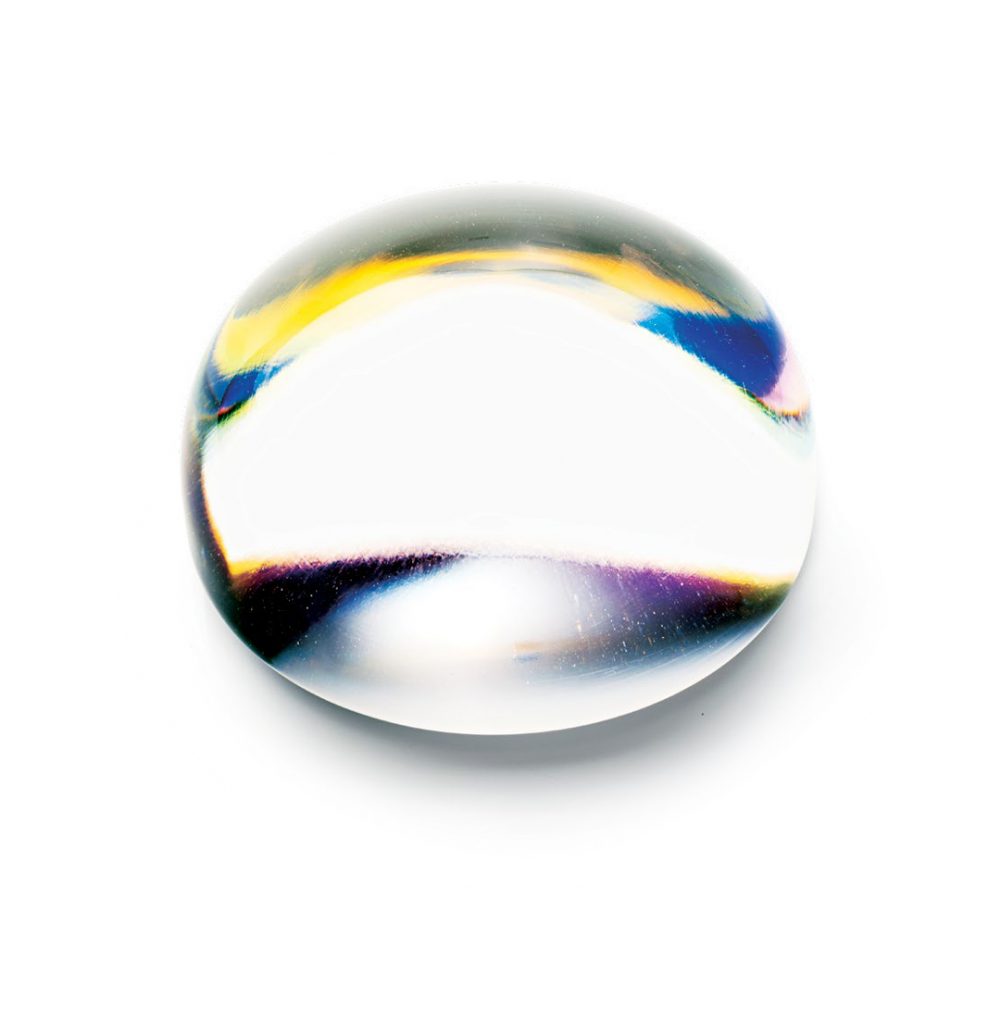

Erie (side view)

Erie (side view)

Hot Sculpted Glass, 8 x 8 x 4” First Light Selection 2018

Erie (top view)

Erie (top view)

Hot Sculpted Glass, 8 x 8 x 4” First Light Selection 2018

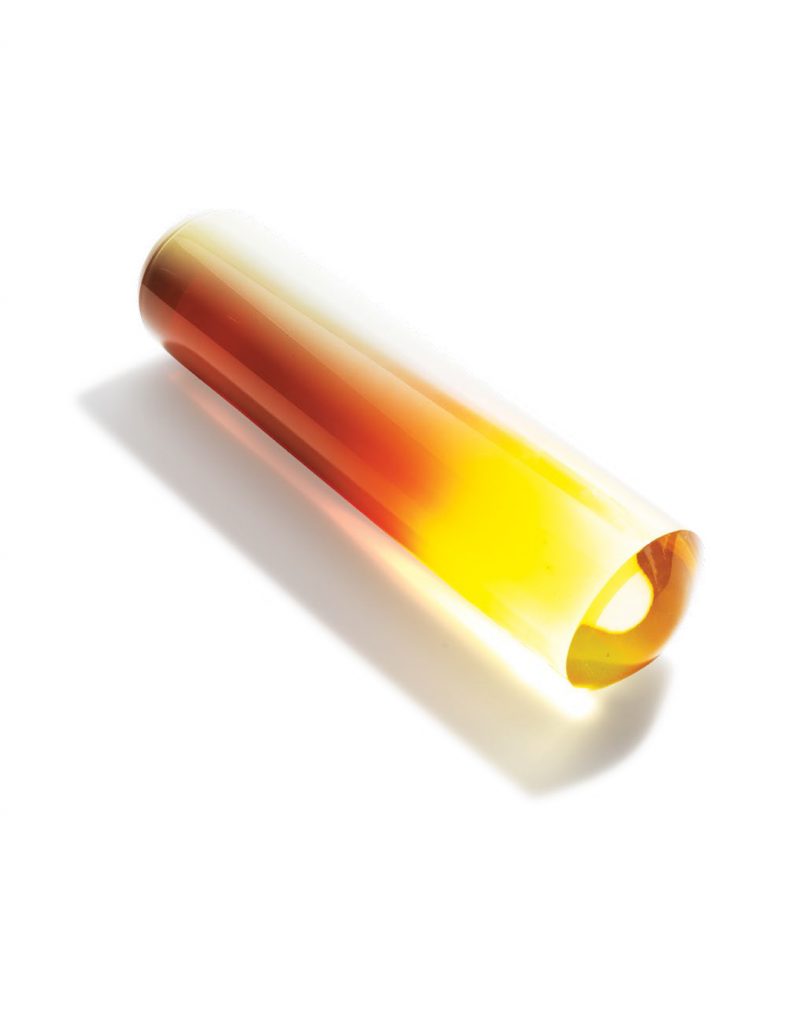

Aphex

Aphex

Hot Sculpted Glass, Cold Worked, 3.5 x 3.5 x 15” First Light Selection 2018

Pleurotus

Pleurotus

Hot Sculpted Glass, 9 x 7.5 x 8.5” First Light Selection 2018

Abyssal

Abyssal

Hot Sculpted Glass, Cold Worked , 8.5 x 4 x 8.5” First Light Selection 2018

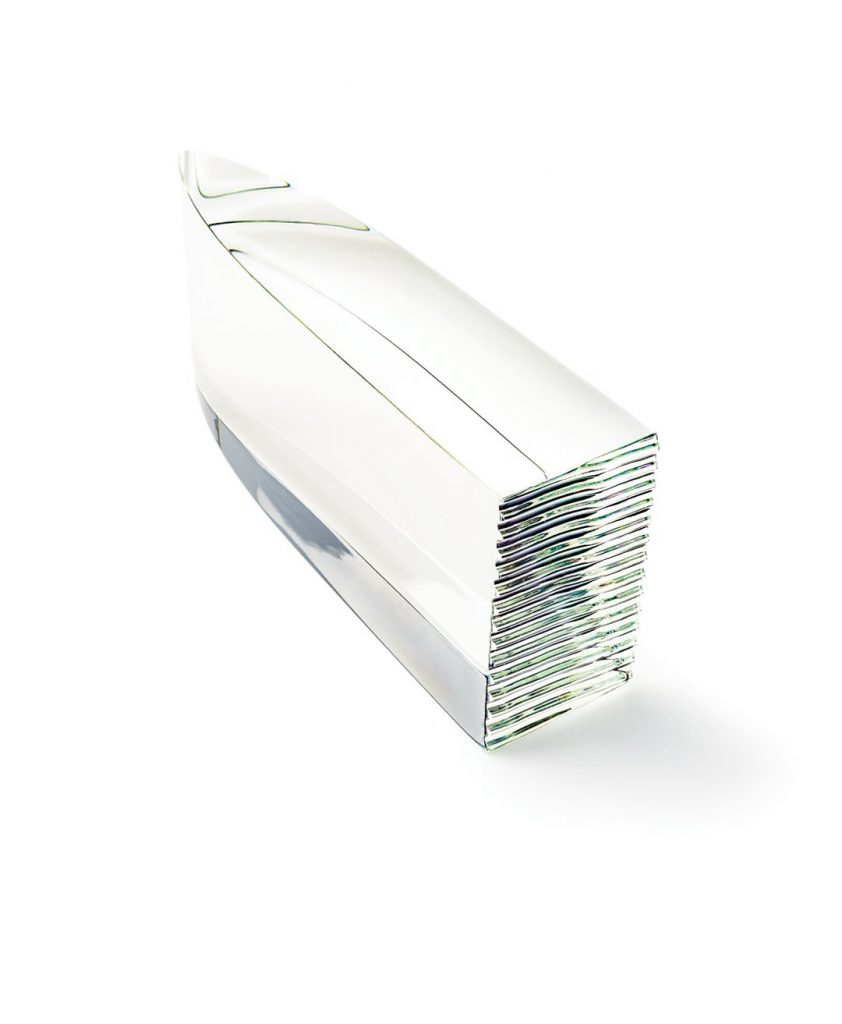

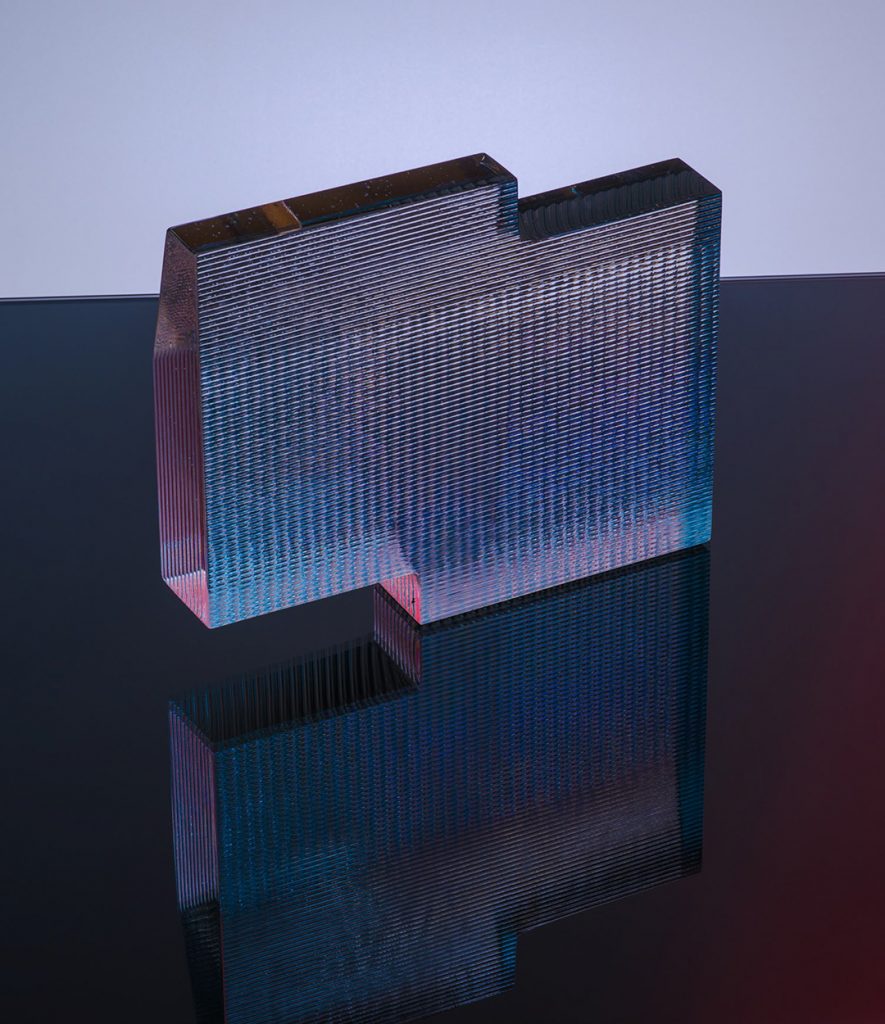

Qu

Qu

Kiln Cast Glass, Cold Worked, 5.5 x 3 x 13.5” First Light Selection 2018

Gyre

Gyre

5 x 9 x 6.5”, Hot sculpted and cold worked glass, 2018

Blur

Blur

7 x 9 x 7”, Hot sculpted and cold worked glass, 2018

Pink Gold Shift

Pink Gold Shift

6 x 10 x 13”, Hot sculpted and cold worked glass, 2016

Gibbous

Gibbous

5 x 9.5 x 8” Hot sculpted and cold worked glass, 2018

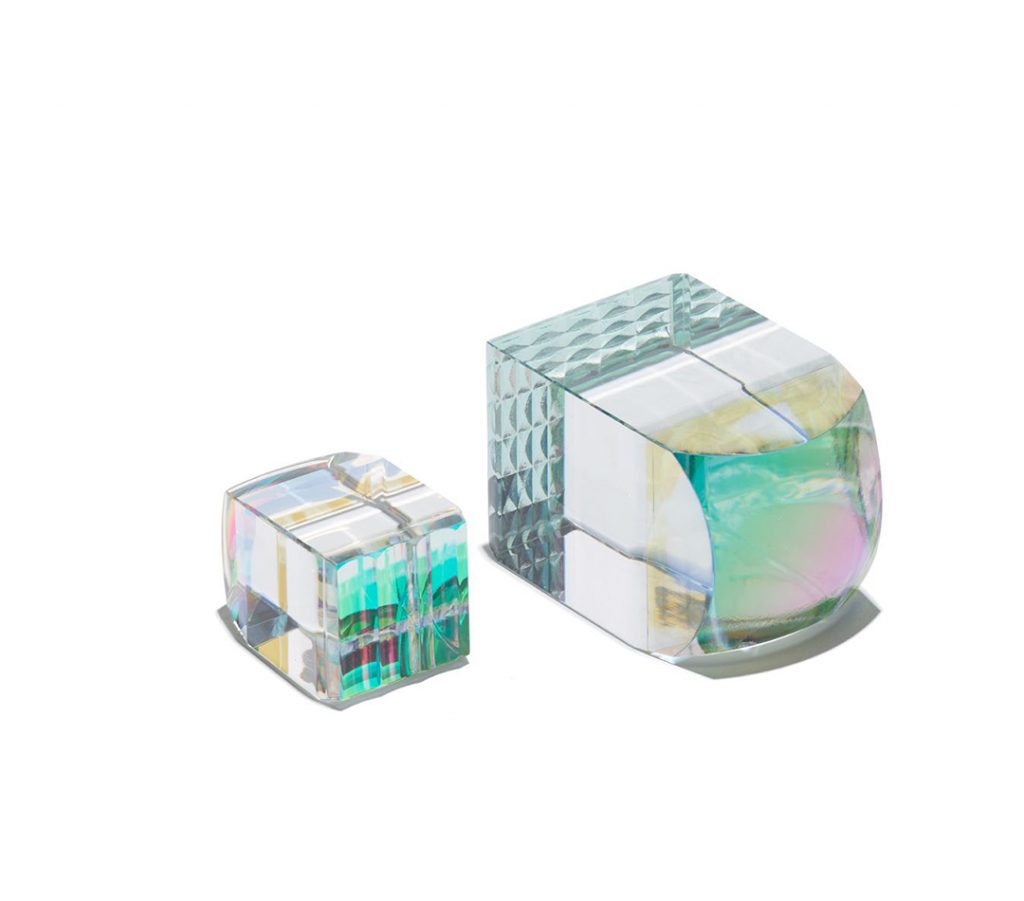

On Squiches

On Squiches

2.5x2.5x3” and 1.5x1.5x2.5”, Kiln cast and cold worked glass, 2016

Bunch

Bunch

6 x 6 x 7”, Hot sculpted glass, 2016

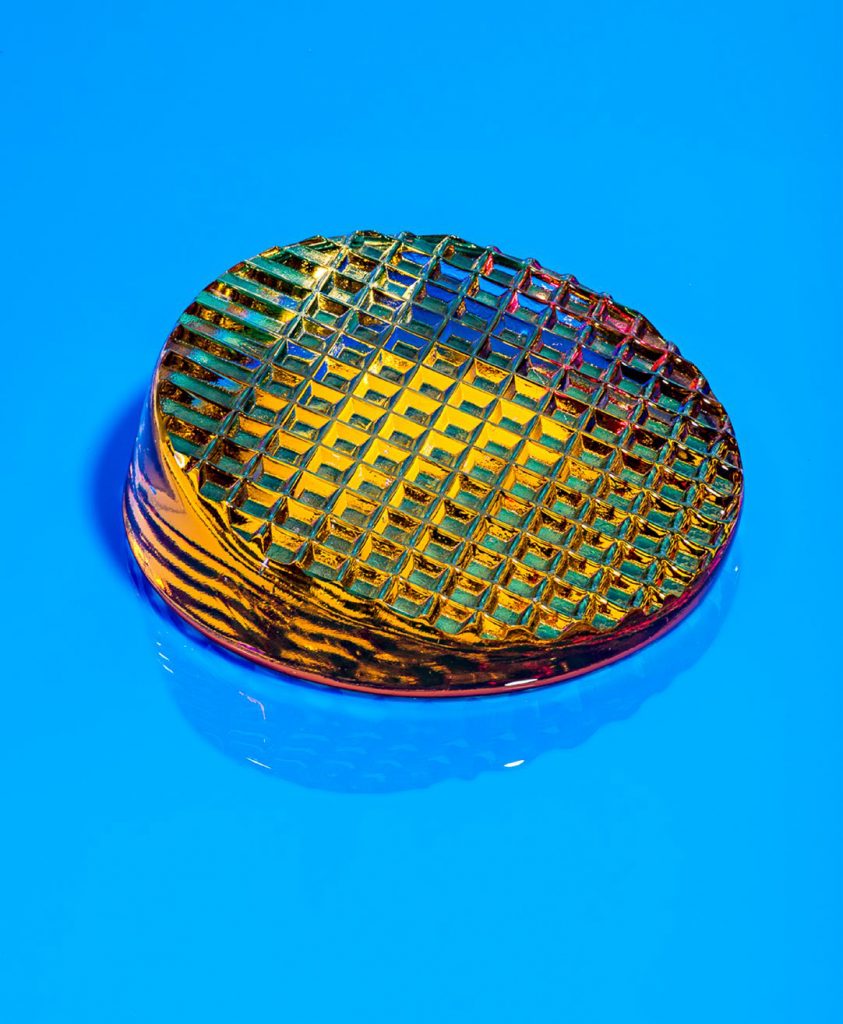

Cordon

Cordon

14 x 14 x 2.5”, Kiln cast and cold worked glass, 2014

Timber

Timber

1 x 1 x 8”, Kiln Cast and cold worked glass, 2015

Vita

Vita

2 x 7 x 7”, Hot Cast and cold worked glass, 2017

Reflect

Reflect

Various dimensions, Blown and cold worked glass, 2018

Blue Water Lens

Blue Water Lens

5 x 10 x 24”, Blown and cold worked glass, 2018

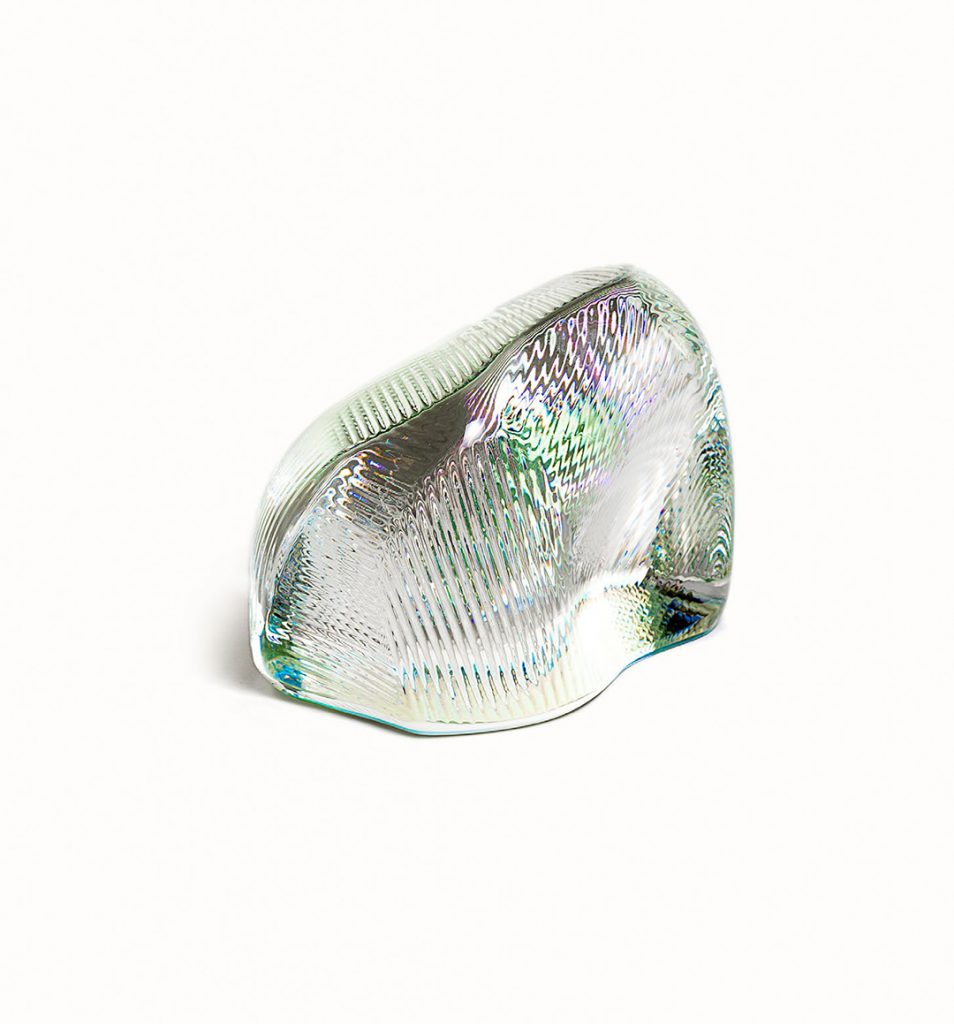

Moire

Moire

2.5 x 9.5 x 13” Hot cast and cold worked glass, 2018

Gibbous

Gibbous

5 x 9.5 x 8”, Hot sculpted and cold worked glass, 2018

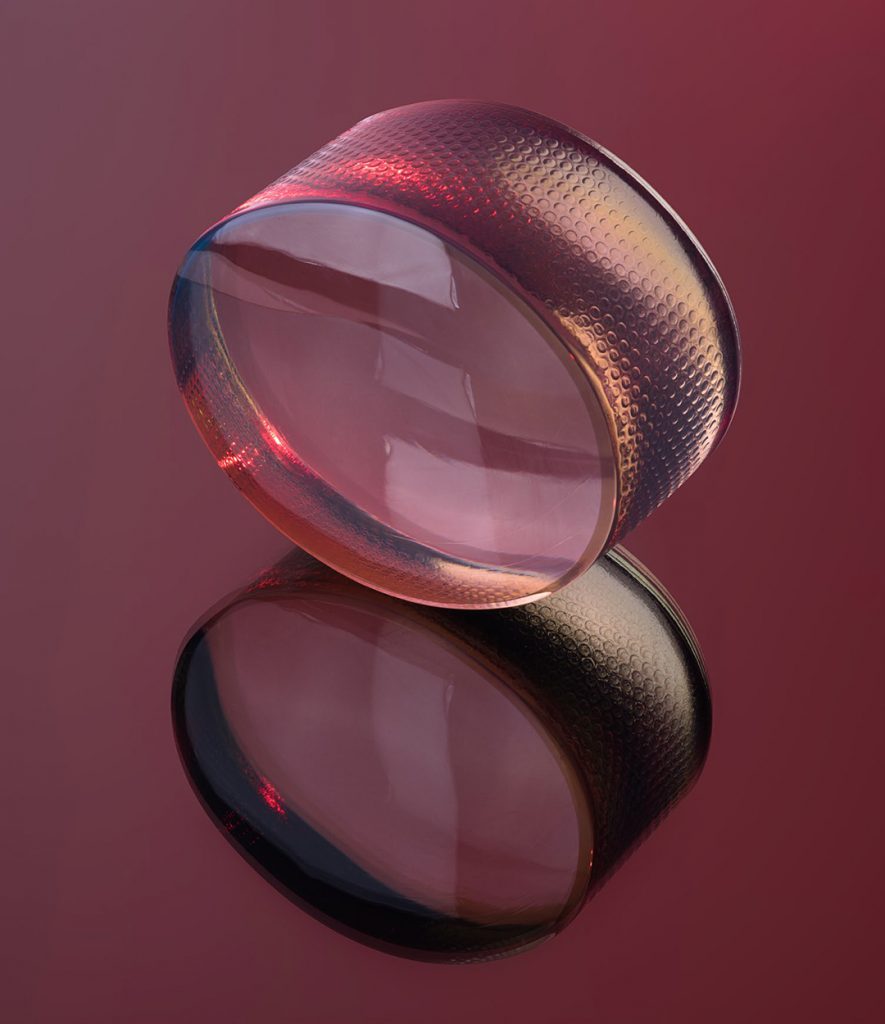

Pensieve

Pensieve

11 x 11 x 4.5”, Hot sculpted and cold worked glass, 2016

Rosate and Flaxen

Rosate and Flaxen

4.5x9x6.5” and 6x7x9.5”, Hot sculpted and cold worked glass, 2017

In Puget Sound, renowned as one of the world’s most creative regions for glass art, artist John Hogan is creating works in cast and blown glass that facilitate and complement the beauty, intensity and radiance of light. Hogan’s work and career has followed a steady, consistent progression, guided by his own passion, a strong education and a string of mentors that have helped shape his outlook and craft.

John Hogan hails from a region steeped in this history and tradition, from an place that has long prided itself on its inven-tion and independence. The Studio Glass Movement was born in the mid-west 50 years ago, when artists in Toledo, Ohio first started making art with glass. Hogan grew up next to a glass-blowing studio and, from the age of six, knew he wanted to be a glass artist. At 15, Hogan enrolled in his first glass blowing courses at the Toledo Museum of Art. Later, he attended Bowling Green University just south of Toledo, majoring in Political Science, with a minor in Fine Arts.

After graduating in 2008, Hogan was drawn to Seattle, to a region known for the depth and strength of its glass arts community. In 2010, he co-founded “5416” studio, named after its Ballard Street address, and was soon showing in local galleries as well as in New York, Miami and Europe. His work, characterized by its subtlety and simplicity, began attracting a following of designers from around the country.

The next stage of Hogan’s education consisted of a series of mentorships and studio studies under leaders of different glass traditions around the world. He worked with artists Osamu and Yumiko Noda at Pilchuck in 2013 and later at their atelier in Niijima. His first two days with the Nodas consisted solely of traditional Japanese calligraphy, a requirement before apprentices were allowed to enter the studio. The Nodas view brush work as an analogue for the fine eye-hand skills needed to craft the most meticulous glass pieces. The Nodas approach to glass was more experimental and free than anything Hogan had yet seen, and their playful, sensitive approach left a lasting impression. Hogan next studied at Novy Bor, in the Czech Republic, in the studio of Milan Handl, study-ing the sophisticated kiln technology Handl used to make large scale cast works. Those techniques would come to both inform and define Hogan’s work, allowing him to use cast glass as a medium to control and manipulate light.

Hogan’s first opportunity to experiment with architecture came with an invitation to work with MOS Architects on a project for the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Together, they created a 16-foot tower in load-bearing, stacked, cast-glass blocks, a conceptual design updating the 1922 competition for an office tower for the Chicago Tribune, one of the landmark events of Modern architecture. Hogan and MOS Architects continue to collaborate, working to further develop and refine the systems they began at the Biennial to build structures and interiors with glass.

The story of Hogan’s collaboration with Westbank and architect James Cheng begins with an exploration that started at the Shangri-La Vancouver. This was a project where Westbank and JKMC Architects first experimented with the layering of screens, a concept they later continued with Kengo Kuma on Alberni by Kengo Kuma, through the Japanese design philosophy of layering. They had been thinking about a screen layer on the podium of their project at Third and Virginia for some time, when a senior Westbank staffer first identified Hogan’s Chicago Biennial designs. On researching his other work, she suggested Hogan might be the artistic collaborator they’d been looking for to help refine this screen concept. Soon Hogan was in conversation with Westbank founder Ian Gillespie, discussing how a glass installation could modify light coming into the building: “We were talking about a second skin, how a veil of silk could be draped over the building podium.” Hogan went back to his studio and produced five concepts, and together, he and Westbank chose Light as a Common Thread, Glass Veil.